NBANBAIndiana’s road to a Finals comeback starts in transition. Can it rediscover its defensive identity in time to force a Game 7?

Getty Images/Ringer illustration

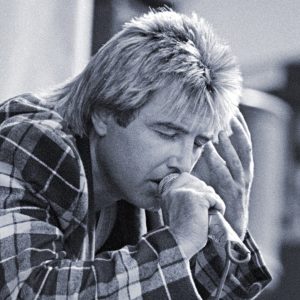

By Michael PinaJune 19, 10:30 am UTC • 8 min

Throughout their Game 5 loss, the Indiana Pacers couldn’t do the one thing that’s helped make these NBA Finals a lot more competitive than most expected them to be: get back on defense. The Oklahoma City Thunder scored more fast-break points (17) on Monday than Indiana had allowed in any game all postseason.

En route to enjoying one of its most efficient performances of the playoffs, Oklahoma City galloped up and down the court, relatively unbothered by scattered defenders who weren’t able to bring the same cohesive, disciplined, communicative effort that was ever present during the series’ first four games. Almost every live-ball turnover was converted into a layup, dunk, or uncontested 3, an unforgiving reminder of how critical transition defense is to the Pacers, who almost definitely won’t survive Game 6 without executing it at the elite level they’ve shown they can.

Both teams play so fast that it sometimes looks like they’re playing on a court covered in coconut oil, but the Thunder, in particular, spent their entire season extending leads in the open floor. They love to run even more than Indiana does, setting up an unstoppable-force-meets-immovable-object confrontation against the Pacers, who allowed the second-fewest fast break points and third-fewest points off turnovers this year.

In the first three rounds, Oklahoma City went scorched earth with its transition offense, the postseason’s most effective, generating 153.4 points per 100 possessions after a turnover and 131.6 after a defensive rebound. In the Finals, those two numbers have plummeted to 105.9 and 112.5, respectively. Put another way: The Pacers have dominated this battle, further establishing themselves as a group that’s most comfortable when thrust into uncomfortable positions. Three of the five lowest fast break point totals produced by any team in these playoffs have come against the Pacers. They held each of their previous opponents to a single fast break basket one time in every round and then limited the Thunder to just four such points in Game 2.

It’s all so much easier said than done, and it’s essential to Indiana’s success. “There’s a reason they’re here,” Thunder head coach Mark Daigneault said. “They do a lot of things well, and one of them is they get back in transition.”

More on the NBA Finals

More on the NBA Finals

The how of the matter goes deeper than clichéd explanations like “hustle” or “care factor.” Those things impact winning, sure, but a team can’t simply decide to be consistently great at getting back in transition. It’s a quality that’s so reliant on other factors, and it’s baked into a roster’s DNA from the day training camp kicks off to, ideally, the night they raise the Larry O’Brien Trophy. The Pacers have spent this entire season limiting oppositional opportunities while also finding ways to get stops when they’re vulnerable. According to Cleaning the Glass, they ranked first in defensive transition frequency during the regular season and have allowed the fewest points per 100 transition plays in the playoffs.

Just about every event in a basketball game is connected to something that already happened. It’s why, as whirling action unfolds from one baseline to the other without much interruption, establishing a functional transition defense is next to impossible for teams that aren’t organized when they have the ball. Floor balance, shot location, spatial awareness, and, obviously, the elimination of live-ball turnovers are all key factors. Throughout these playoffs and most of the regular season, Indiana checked off every box. “I think it starts with their offense,” Thunder guard Alex Caruso said.

The Pacers generally take care of the ball and don’t attempt a bunch of field goals at the rim or drive into the paint as often as other teams; second-chance opportunities are nice but ultimately a secondary objective. During the regular season, Indiana ranked 29th in offensive rebound rate and third in turnover rate. That’s a good place to start! Also, efficiently making shots—as the Pacers do from just about wherever they launch them—gives them a few extra beats to get back and avoid unfavorable cross matches. It’s an understandable albeit ironic belief system for Indy to embrace. Here’s a team that never takes its foot off the gas that’s using firsthand knowledge of how destructive offensive pace can be and turning around and doing everything it can to keep its opponent from hurting it in a similar way. From speed demons to inertia advocates in the blink of an eye.

“We work on it a lot,” Pacers head coach Rick Carlisle said. “What I’ve learned over the years is that teams that play fast tend to have a good kind of foundation to be a good [defensive] transition team.”

Being solid in transition is less about getting an immediate stop and more about curtailing an initial rush and then forcing the offense to execute in the half court; the less time there is on the shot clock, the harder it is to score. No team is better at this than the Pacers:

Even after Indiana misses a shot, the defense is often so frazzled from the experience of guarding its frantic style that it isn’t arranged well enough to run back and get a solid shot the other way. The way the Pacers attack—constantly moving on and away from the ball with screens, cuts, pitches, and handoffs—makes it so hard for any opponent not to feel like they’re falling out of a washing machine.

“I think they do a good job of putting teams behind the ball, putting teams in actions, whether they’re chasing and maybe not influencing,” Caruso continued. “From there, they usually get good shots and efficient shots. Even then, if they’re not, they have you moved around to where it’s not the same scenario when you’re breaking out.”

Combine that with Indiana’s incessant ball pressure, and it’s hard for opponents to get any momentum from makes or misses. “[The coaches] just want us to pick up full court and get back and just affect the ball all the way up and down the court,” Pacers guard Ben Sheppard told The Ringer. “Coach uses the term ‘94 feet.’ We should be playing 94 feet the whole game. It’s a fun way to play.” It’s not just a mantra but a strategy. “I would say it’s a lot of technique, just in terms of turning the ball handler up and down the court and just wearing him out, getting into their legs,” Sheppard noted.

Depending on where they are when the shot goes up, Indiana tries to send two players back as quickly as possible. The coaching staff emphasizes it daily and goes over mistakes that need to be called out.

“There’s spots where you crash [the boards] from, but the opposite side just gets back if you’re above the break,” Pacers guard T.J. McConnell told The Ringer. “Obviously, if you’re at the top of the key, probably want to get back. … It’s just a priority in this league because you’re going against the best players in the world, and if you let them get out in transition, on a fast break with numbers, typically, it’s not gonna turn out well for you.”

In addition to picking up full court whenever it can, Indiana can show a crowd and load to the ball. “A couple times last night, I’m bringing it up and there’s a guy in each gap,” Caruso said after Game 3. “There’s nowhere to find a crease early in the possession.”

In 103 total games this season, the Pacers have been at even strength getting back in transition on a league-high 81.0 percent of their possessions, according to Sportradar. What this essentially means is that they do an excellent job of not allowing their opponent any advantage when the ball crosses half court.

The Pacers will crash from the corner when nobody on the Thunder boxes them out, but they’re mostly better off when those players ignore the chance for a rebound, put their heads down, and sprint back instead. Watch this play from Game 3. If Sheppard hadn’t hustled back to cut off Caruso and let Indiana’s defense settle down and force a turnover, the Thunder probably would have scored:

It’s a mindset, too, that’s been instilled and reiterated by coaches and teammates and that’s peaked at the perfect time. Years from now, the first thing people will remember about Indiana’s shocking Game 1 win will be Tyrese Haliburton’s go-ahead jumper with 0.3 seconds on the clock. But the Pacers were able to win that game because they conceded only nine points off 19 turnovers in the first half. “I mean, some of our turnovers have been so violently bad that Oklahoma hasn’t even had a chance to catch the ball,” Carlisle said.

“As NBA players, just as basketball players in general, it’s easy to make a mistake and dwell on it, give up a bucket or whatever,” Haliburton said. “I feel like we do a great job of getting to the next play. Coach always preaches that. It’s really important here in our organization.

“Honestly, if you make a mistake as a basketball player, the first response should be how to fix it. More times than not, if you turn the ball over, make a dumb play offensively, if you get it back defensively, that kind of makes up for it a little bit.”

On the surface, the Pacers look like a reckless bunch. They accelerate into chaos and emerge on the other side without a single bruise. None of it would be possible if they didn’t also collectively buy into the other side of that coin: Indiana can play as fast as it wants on offense, but all that effort is for naught sans structure and connectivity coming back the other way. Incredible transition defense is, in many ways, the most important part of its identity. Remove it from the equation, and so much of how it plays would flop like a house of cards.

If the Pacers play again like they did in Game 5, it’d virtually guarantee the Thunder their first championship. The good news for the Pacers there, though, is that so much about that loss was an aberration. Oklahoma City very well may win this series, but it’d be something of a shock if it did without having to overcome a defense that, for the most part, has done an excellent job of taking easy chances off the table.

Michael Pina is a senior staff writer at The Ringer who covers the NBA.