Before playing The Last of Us, I had never thought that a video game could be a work of art.

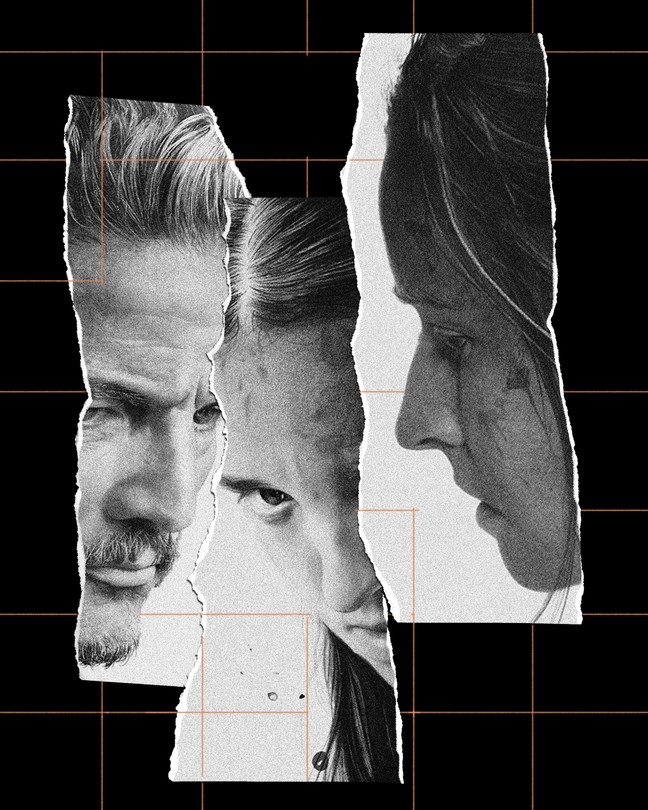

Illustration by The Atlantic. Source: HBO.

This article contains spoilers through Season 1 of The Last of Us.

In the final episode of Season 1 of The Last of Us, the most emotionally wrenching zombie-apocalypse TV show ever made, a loner named Joel stalks through a hospital, his face as emotionless as the Terminator’s, killing everyone in his way. He is trying to save a young woman named Ellie, who holds the secret to curing the zombie plague, but to make that antidote, she has to die, and Joel would rather let his species go extinct than lose her. I recently asked the actor who plays Joel, Pedro Pascal, how he found a way to justify his character’s rampage. He responded: “I understand why he did it, but I can’t justify it.”

He should have asked me. As I told myself every time I saved Ellie, if you truly love someone, killing for them is easy.

The Last of Us is based on a video game of the same name, and the second season of the series premieres this week. Before The Last of Us, I had never been a serious gamer, for the same reason I don’t do cocaine: I’m an ADHD-addled depressive with escape fantasies, and if I tried it, I might never come back. So, outside of Mario Kart races with my kids, I abstained. But on one of the uncountable empty days of the early coronavirus pandemic, I put down $300 to buy a Playstation 4, which came prepackaged with The Last of Us. The game booted up and showed me an open window, its curtain blowing in a light breeze. I was told to “Press Any Button.” I did.

A young girl named Sarah sits in an empty room. Her father, Joel, enters. She gives him a watch as a birthday present. He likes it. She falls asleep, and he gently tucks her into bed. What was this—an interactive simulation of a Hallmark movie?

Read: Easy mode is actually for adults

Sarah wakes up later that night, alone. She gets out of bed and then … stands there, not moving. I realized this was on me. I pressed the joystick in my hand. She moved. She, or I, or we, went downstairs to look for her, or our, father.

Then the first sirens blared outside. News reports flashed on the TV. Joel ran in, panicked. A neighbor crashed through the sliding door, crazed, howling like an animal. Joel killed him. This was more like it. Next we were in a truck, trying to get someplace safe, and the truck crashed, and now I was Joel, fleeing with Sarah in my arms as a horde of bloodthirsty people tried to bite us and a soldier shot Sarah and she died in Joel’s arms or my arms and the screen went black and I realized that this was not Mario Kart.

Over the next days and weeks I would labor until my obligations to work and family were done and I could turn on the console and turn off the lights and be Joel again. By now he was a smuggler, traveling with a girl called Ellie across a bleak landscape filled with monsters that were once people and monsters who were still people, doing everything he could to keep her alive.

After I had finally saved Ellie, and doomed humanity while doing it, I found myself back in my own world, watching the credits roll and feeling exhilaration and regret, each as vivid to me as I had ever experienced in my real life.

I couldn’t remember when I had been so affected by a work of art. Or when I had ever thought that a video game could be a work of art.

Neil Druckmann was born in Israel in 1978, and, like most ’80s kids, he became fascinated with comic books and video games, which helped him learn his idiomatic but still accented English. When his family relocated to Miami, he attended college for a criminal-science degree but found himself drawn to the gaming industry, eventually getting a master’s degree in entertainment technology at Carnegie Mellon. In 2004, he joined the Naughty Dog game studio as an intern, and quickly rose in the company, designing and programming games, including its Uncharted series of Indiana Jones–like adventures. And during all that time, he was piecing together a story—or in the clinical language of modern media, an “IP,” or intellectual property—of his own.

His inspirations were an obscure but beloved Japanese game called Ico, from the early 2000s, in which the hero leads an imprisoned princess by the hand out of a huge castle; Frank Miller’s comic book Sin City, featuring a violence-scarred cop who protects a little girl; and the universe of zombie stories, most importantly George Romero’s Living Dead movies. The game would be graphically sophisticated and expertly designed by Naughty Dog’s team of artists and engineers. But the real innovation was its core subject matter, something that may have been entirely new to the industry:

“The game,” he says, “is about the unconditional love a parent has for a child.”

Druckmann is, along with Craig Mazin, the co-creator, executive producer, and writer of the HBO adaptation. (I hosted a podcast with Mazin in 2019 about his HBO miniseries Chernobyl.) I spoke with them both during post production for Season 2 of The Last of Us. The show is Druckmann’s first foray into traditional filmmaking, and I asked him about the difference between creating a story as a game to play and as a TV show to simply watch. He told me that from the very earliest conceptions of the game, he had been sketching out the “mechanics” of Joel and Ellie’s relationship.

Was that another term for what a screenwriter might call story beats or plot points?

“No,” he said, speaking patiently, as he would to someone who hadn’t learned English from video games. “I mean interactive mechanics: How do we put certain interactive elements on the stick?” (Meaning, literally, in the hands of the player, holding his joystick controller.) “How do we use that dimension? People that actually have kids know immediately: You would do anything for this other person. How do we make the player feel that?”

He pointed to a moment midway through the game when Joel and Ellie are exploring an abandoned hotel, and Joel falls down an elevator shaft, and then has to fight his way from the basement back to Ellie. It’s the first time in the game that the two are separated. “You feel Ellie not being around you,” Druckmann said. “And you miss her.”

I remember that moment vividly, the vertiginous feeling of not just falling but falling away from Ellie, whom by then I had saved from death many times, and I felt panic and anxiety because she was alone in a world filled with predators … and I had to get back to her.

I have never been angrier, or more impressed, at being so profoundly and successfully manipulated.

Many video-game adaptations in TV and film have been profitable; few have been critically acclaimed; a couple, like 1993’s Super Mario Bros., with Bob Hoskins and John Leguizamo as the titular plumbers, have been epoch-defining disasters. The pitfalls are many, the most obvious being that a game’s appeal is that it’s something you play. Can anything a writer or director comes up with be more fun than slaying the dragon (or zombies, or aliens) yourself? But at the center of the problem is the protagonist, a human-shaped frame intentionally left empty so that you, the player, can fill it.

“For example, when they adapted Halo, they had a complication,” Mazin told me, talking about the popular first-person-shooter game. “They had a hero whose face you never saw and whose voice you never heard. Then you’ve got to invent somebody, and you’ve got to think, What is his face and what does he sound like and what does he want and what does he say?” Halo ran for two seasons on Paramount Plus before being canceled.

The Last of Us posed the reverse challenge: one of abundance. Joel and Ellie aren’t faceless and voiceless human suits for the player to wear, but fully fleshed out, living people played via motion capture by the actors Troy Baker and Ashley Johnson. As players first inhabit Joel, then Ellie, then Joel again, they follow a linear trajectory, designed to create meaning not only on the screen, but also in them. The interaction goes both ways, as the players steer the game and the game steers them.The result is an experience of fear, anxiety, relief, rage, and finally, Druckmann’s carefully engineered final state: unconditional if murderous love.

But the viewers of a TV show can’t fall down a shaft and be separated from a character just so they will miss her, let alone hold the character’s choices in their own hands. All a TV show can do is show other people making those choices, and hope the audience follows along. It’s the difference between describing what gravity feels like and throwing somebody off a cliff.

For the show, Mazin and Druckmann faithfully re-created many famous scenes and much of the dialogue from the game—sometimes down to costumes, set design, and camera angles. They didn’t do this, they assured me, to please fans of the game who might be upset at the omission, for example, of the moment when Joel and Ellie find a herd of wild giraffes descended from zoo animals in Salt Lake City. They re-created that scene because, as the saying goes, if something ain’t broke, rent an actual giraffe. “We don’t sit there and go, ‘Ah, shit, this is something that is a waste of time, but the fans would love it,’” Mazin said. “If there’s fan service, the fan is me.”

They also expanded the story laterally. Because they are no longer avatars for the viewer, the principal characters can be less admirable. As played by Bella Ramsey, Ellie seems older than the waifish game character, with a reckless temper and a willingness to deceive. Pascal’s Joel is more emotionally reserved and wary than Troy Baker’s, and at the same time, more callous and seething with anger. In the show, someone says that Joel is the only thing in the desolate waste that scares another smuggler … and you believe it.

In the game, Druckmann told me, he insisted that the player would see only what the protagonist sees, so they’d have the same reaction to whatever lurked around the next corner. The TV show, though, delves into other storylines, most famously in the episode “Long, Long Time.” Early on in the game, Joel and Ellie pick up supplies and a vehicle from Bill, a loner in a fortified small town. Bill mentions that his “partner,” Frank, has left. From that scrap of backstory, the show spins out a love story between the deeply closeted survivalist Bill (Nick Offerman, who won an Emmy for the role), and Frank (Murray Bartlett).To pause the zombie fighting and dwell on a long-term romance was a remarkable gamble. If the elevator-shaft sequence in the game is impossible to replicate on TV, this episode’s slow conjuring of grace in the midst of ruin would be impossible in a game.

Another difference is a significant reduction of the body count. I asked Druckmann and Mazin about all the violence in the game, and they almost laughed, as if I was asking a soccer coach why his players don’t just throw the ball. That’s how games are played. “The violence is problem-solving,” Mazin said. “That’s the play. That’s the fun part.”

But in real life, anyone who killed as many people as Joel and eventually Ellie do in the game would be reduced to a traumatized, gibbering husk. “In the show, we actually talked about how to make every single act of violence matter,” Mazin went on. “Every single one changes not only the person doing it, but the relationship between Joel and Ellie.”

Mazin and Druckmann aren’t always successful. One episode’s climactic set piece re-creates a sequence in the game in which Joel, perched with a sniper rifle above a mass melee, picks off assailants as they threaten Ellie. It’s one of the very few moments when the show’s video-game roots show: No sane person would fire that many rounds so close to somebody he cared for unless he knew that if he hit her, time would reset and he could try again.

But there are many instances in which, as Mazin says, the violence ratchets the relationships into a new state. For example: a brutal fight in which someone is about to kill Joel before Ellie shoots him with a gun she’s secreted away. The man howls in agony, sobbing and begging for his life until Joel stabs him to death. From that moment, Ellie is no longer “cargo,” as Joel has called her; she has saved his life, and helped him take someone else’s, and the trauma yokes them together.

HBO is being tight-lipped about Season 2, but it is based on The Last of Us Part II, the sequel game, which was released in 2020. If it follows that story as closely as the first season followed the original game, we know some of what to expect. The first game was about unconditional love; the second was about something Druckmann says he learned about while growing up in the West Bank: tribal rage, the desire for vengeance, and how violence begets more violence.

The central, violent conflict is between Ellie and another young woman named Abby, something once unheard of in the male-dominated space of video gaming, and still rare in prestige TV.

From the July/August 2023 issue: ‘Hell welcomes all’

Druckmann brought on Halley Gross, a writer for HBO’s Westworld, to help write the second game, and hired her again for the show. He told me that in addition to needing help organizing a script with far more characters and branching storylines, “I also knew that I wanted to tell the story of Ellie and Abby and put these two women through the ringer – physically and emotionally. I believed that I would approach the material with a higher level of confidence if I could do it with a female co-writer.”

As Season 2 jumps forward five years, we realize that Ellie is not just a character who’s had some exciting adventures and is about to have some more. After her bloody salvation, she is “locked in trauma,” Gross told me. “She cannot outrun this. She cannot outthink this.”

The Last of Us Part 2 was as revolutionary as the first game, but in new ways. If the first game was designed to make you feel love, the second asks the player to experience anger, hatred, and eventually even guilt, as their transgressions make Joel’s rampage at the end of Season 1 seem like an easy call.

I’ll be watching what happens next with excitement and dread. (Gamers know why). But—like others who spent many hours on the stick—I know I’ll feel some nostalgia for the time when I lived it all myself.