JALEN HURTS ISN’T at Disney World. On a gray March afternoon in Philadelphia, I find him at the Fitler Club, a sleek, members-only lifestyle hub hidden in a Center City alley overlooking the Schuylkill River. Hurts is seated in an industrial style conference room against a backdrop of steel, locker-style cages. He has the relaxed look of an offseason athlete: all-black Jordan sweatsuit over a white tee, paired with Air Force Ones.

When I enter the room, his large hands are casually tapping an iPad that has a case covered in motivational quotes. On the back, a black-and-white sticker reads, in all caps, “if your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a leader.” Beside it: two crumpled, handwritten Post-it notes—one on expectations, another on integrity. A fresh pink Post-it encourages: “You are exactly where you are supposed to be. I love you. Follow God! I follow you.” It’s signed simply “B”—his wife, Bryonna Burrows.

With Hurts six weeks removed from his biggest career win after five seasons with the Eagles, you might think he would still be riding the high of being named Super Bowl MVP. After years of intense scrutiny about his game, a crushing Super Bowl loss two years ago, and a transitional 2023–24 season, now that the team has soared to a championship on his wings, how does he feel? Hoorah.

“I allocated five days of celebration,” he says, then he actually lists just four: the locker room, the team parade, and (yes) the Disney parade. “Four is the ring ceremony. That’s it.” Then it was back to work: training, sleep, meetings, study, repeat. Even during the locker room festivities, while teammates partied shirtless and sprayed Ace of Spades, Hurts kept his shirt on, his joy contained. You’ve probably seen the photo of him sitting on the floor, cigar in mouth, soaking it all in. If you expected one of the NFL’s most unreadable players to show a visible zest post-victory, you were mistaken. Days later, during his post–Super Bowl press run, Gayle King, noting his demeanor, asked him on CBS Mornings, “But you are happy about this, right?” He responded, “One hundred percent,” but it wasn’t very convincing. (Those with a reserved disposition understand he’s happy inside.) Hurts jokes that lately his management team has been calling him demure. “I don’t know that I’ve ever used that in a sentence,” he deadpans.

GET JALEN’S LOOK: Rick Owens T-shirt; Hurts’s own jewelry.

There’s a T-shirt for sale online showing Hurts’s straight-faced expression for various emotions—sad, happy, excited—all the images identical except one, where he’s grinning: “4th and 1.” It’s fitting for a couple of reasons. It makes fun of Hurts’s penchant for keeping his emotions in check, and it speaks to the success the Eagles had with their famous “tush push” last season—powered in part by Hurts’s 6’1″, 223-pound frame and monster quads, capable of squatting 620 pounds. It was successful 39 out of 48 times, resulting in a first down or a touchdown, according to CBS Sports. Eight of the times it failed, the team repeated the play and earned a first down or a touchdown. The shirt also recognizes Hurts’s mindset and appreciation for process: Once the Eagles get to tush push territory, good things happen.

On our televisions and in our feeds, the NFL isn’t just a sport, and top football players aren’t just players—they’re brands and cultural figures. Hurts has endorsements, but his visibility is not as high as Patrick Mahomes’s or Travis Kelce’s. He’s a private guy who seems to have no desire to lean into memes about his name or do goofy insurance ads. When I ask Hurts if he’s interested in being the face of the NFL, he says, “Hmm.” Then a definitive “No.” But when you’re the MVP of the Super Bowl, you are the face of the NFL. For a Black quarterback, of course, the question is even more soul-searching, rubbing up against the all-American quarterback ideal. Hurts knows. “You hear people talk about Doug Williams, Warren Moon, and Randall Cunningham and their tenures quarterbacking in the NFL, and those are all opportunities to learn from. It’s history,” he says diplomatically.

Kevin Sabitus//Getty Images

Kevin Sabitus//Getty Images

In Super Bowl LIX, Jalen Hurts passed for 221 yards and two touchdowns while completing 17-of-22 passes. He also rushed for 72 yards and a score en route to being named Super Bowl MVP .

To cement his position in the sport and the culture, Hurts must keep winning and trusting his process. He tells me he’s not chasing a set number of rings or fixated on building his brand. His focus this offseason is on incremental growth. “It’s hard for me to enjoy certain successes in real time, because I’m in pursuit of something,” he says. “You have to have a constant drive. It has to burn within you to where you don’t want to stop. How can I better myself? How can I evolve? It’s days and nights and years of hard work paying off. Now, what do I have to do the next time around?” It’s not difficult to imagine Hurts as an NFL cyborg, a first down–hunting Terminator who absolutely will not stop, ever.

It’s a work ethic nurtured by his dad (who’s also his longtime football coach) and galvanized by the grit that comes from a national college championship game benching. “I’m not ever in a place where I’m the same person,” he says. “Those calluses, those bumps, those bruises—they’re all necessary for you to be who you’re supposed to be. You have to embrace them.” This demure, sphinxlike superstar with the Mona Lisa smile is winning in his own way, sticking to what’s worked. But now that he’s tasted success, does Jalen Hurts have to stay so serious to maintain it?

TO FIND THE roots of Hurts’s 4th-and-1 mentality, you must go to Channelview, Texas, a suburb 16 miles east of Houston, where he started as a ball boy, watching his dad, Averion Sr., endure seasons of highs and lows as coach of the Channelview Falcons. When Hurts joined the team as a quarterback in his freshman year, he was stepping into the shoes of his brother, Averion Jr., who’s four years older. He remembers the team’s losses viscerally. “I saw my father and the team go through a long period of losing and trying to figure things out, and I knew it wasn’t gonna go that way for me,” he says. “What told me that, I don’t know. My confidence, maybe.” When I ask him if any high school sports losses still weigh on him, he replies instantly, “It’s two of ’em.”

He smiles wistfully, as if preparing to share a war story. In conversation, Hurts shifts between several subtle facial expressions: a half-smirk, a knowing smile, and a broad dimpled grin that, when deployed, feels deserving of its own parade.

About those losses: The first was in ninth grade, when he ran the anchor leg in a track relay. He describes it poetically: “All year, I killed everybody. Brought it home. I go catch people. Brought it home.” But in the district meet, a runner he’d beaten all year flipped the script. “It killed me that he caught me at the very final five meters,” he says. “It killed me.” The second was in sophomore year, when the Falcons started strong at 4-0, then tanked the last six games. “Not making it to the playoffs lit a fire in me. Losing lit a fire in me,” he says. “Those are the little things. Chips of wood on the fire.”

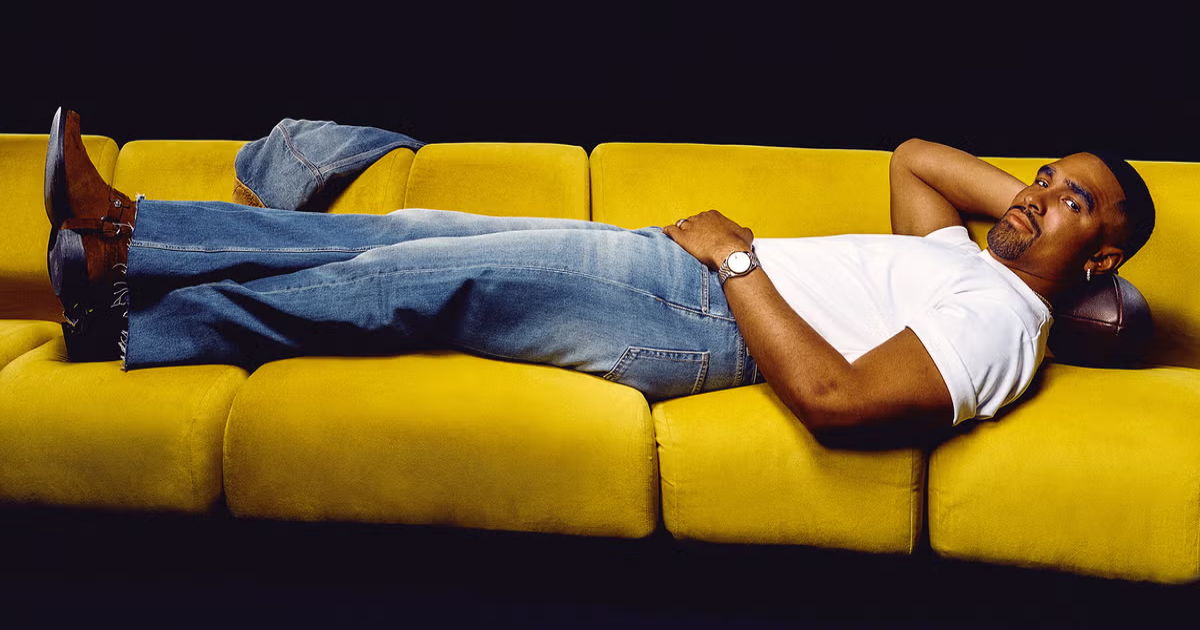

Joshua Kissi

Joshua Kissi

GET JALEN’S LOOK: Alexander McQueen jacket; Alexander McQueen jeans; Uniqlo T-shirt; Toga Virilis boots; Rolex watch.

The frustration ran so deep that he quit basketball and baseball. “My father was messed up about it. ‘You letting go baseball?!’ ” Hurts recalls fondly, looking down at the table. He’s not one to gesticulate, and he speaks in a confident, even-toned Texas drawl, taking cosmic pauses, and once his thought is complete, he meets your gaze with penetrating focus. “Baseball was my first love. My father knew I was serious about football when I let that go.”

His father taught him that having a work ethic was on the players. Development became essential for Hurts. Wins and losses allowed his brain to complete another software update. “I was the one that listened. I was the one who bought in. I was the one who had that respect for protocol, seniority, and authority,” he says. “Those things forged my mindset.” Mentally he was sharp, but his physical strength lagged until his father had him join the school’s powerlifting team—by 15, he was squatting 500 pounds. The more that strength transformed Hurts’s game, the more he enjoyed building his body into a multi-tooled weapon.

“Those CALLUSES, those BUMPS, those BRUISES—they’re all NECESSARY.”

What attracted him to the University of Alabama was Coach Nick Saban’s five pillars of success: commitment, discipline, effort, toughness, and pride. It wasn’t far from Hurts’s own approach. “Just refined,” he says. But as football fans know intimately, not all went to plan at Alabama. Today, Hurts can finally laugh at the moment that made him cry. Over two years, he had led the Crimson Tide to a 26-2 record and shattered the program’s single-season passing mark his sophomore year. Then came the national championship game against Georgia. After a miserable first half and a 13-0 deficit, Saban benched Hurts for freshman Tua Tagovailoa, leaving Hurts to watch from the sideline as the Tide stormed back to win. Publicly, he kept his composure. Privately, he felt destroyed. “A lot of my first impression of the world was getting pulled out of that game,” he says. “As competitive as I am and as hard as I am on myself, I only lost two games and I’ve been replaced.” He laughs, incredulous.

“Don’t get me wrong—I was joyful for my team and happy we won a championship,” he says. “When you get with your family, you see a different set of emotions. They’re thinking about Jalen Hurts and not the team. That’s a thousand percent fair.” Later, back at the team hotel, the weight of it hit him. He broke down in the arms of his father. “I remember I cried on his shoulder,” Hurts says. “I cried, asking him what we were gonna do. What was I gonna do? I say this like, once I process something, I can move on.” His dad told him that they would fight. “It takes courage to do that,” Hurts says. “I respected that because that paved the way for me to believe I could overcome anything.”

Hurts on the sideline with Tua Tagovailoa, who replaced Hurts in the second half as Alabama came from behind to beat Georgia and win the national championship in 2018.

The benching—and his father’s belief in him—is the Jalen Hurts version of being bitten by a radioactive spider. It set the stage for one of football’s greatest redemption arcs. After a year sitting on the Alabama bench and soaking up knowledge, he finished his college football career at Oklahoma. Coach Lincoln Riley encouraged Hurts to embrace the art of preparation and loosen up his playing style. Hurts led the Sooners to 12-1 and finished the year as a Heisman Trophy runner-up to Joe Burrow. Even his major at Oklahoma, in human relations, was deliberate, a way to learn the people-management skills that would help him as a quarterback.

By the time the Eagles drafted Hurts with the 53rd overall pick in 2020, his lessons had crystallized into a code: Control what you can control. He took over the starting job from Carson Wentz at the end of his first season and has progressed every year. He led the Eagles to the 2023 Super Bowl, where they lost to the Kansas City Chiefs. Every defeat is an opportunity to correct course: That’s the mental process that kicks in, including after his late-game fumble, which led to a Chiefs touchdown. “You gotta do your research so you can prevent it from happening again,” he says about that Super Bowl loss. “So many variables go into a decision being made, so it’s not something that I hold my head on.” Cosmic pause; he eyes the lemon water in front of him. “It’s a ‘maybe if I would have.’ Not a regret, but a maybe. No regrets, because every experience prepares you for the next thing. I know if I would have, this would happen in terms of what I could control.”

After that loss, Hurts fine-tuned his approach, aiming for greater efficiency. “That’s an example of me having a great game statistically and feeling empty,” he says. (His three rushing touchdowns set a Super Bowl record for a quarterback.) “I value winning.” He repeats it. “I value winning. Everything is centered upon that.” Losing impacts him profoundly, to the extent that he almost sees self-improvement as a way to rewrite history: If he can refine every detail of his game, he will have cleared a path to victory while at the same time outworking his past self.

Seven years after his Bama benching and two years after that Super Bowl loss to the Chiefs, there were more tears at a championship game. “From a grand point of view, the triumph and the journey and what it took, no one sees or knows or can comprehend,” Hurts says. “But ultimately, I’m grateful for the challenges because it did something for me that success never would have.”

This time, Averion Sr. wept on his son’s shoulder, in a shower of confetti at New Orleans’s Superdome, celebrating Hurts’s first Super Bowl win and first MVP trophy, in a dominant performance against the Chiefs. “That mirror moment of crying on his shoulder and asking what we would do and him refueling me in a way and saying, ‘Don’t forget who you are. You’re gonna fight’—him re-instilling that belief in me meant the world to me. Everything changed mentally for me.” Hurts told me that all he said to his dad was “It’s been a ride.” Then he deploys the broad dimpled grin.

NOW THAT HURTS has completed his four days of Super Bowl celebration, he’s into the main thing of the off-season: incremental improvement, working with quarterback trainer Taylor Kelly out in Los Angeles. Their focus in March was on fine-tuning his mechanics, footwork, and shoulder mobility and strength. “The last three years, they’ve gone far in the season, so we have to manage those throws to make sure we’re not overdoing it,” says Kelly. “We’re hitting about 120 reps in a week and making sure those reps are precise.”

The emphasis is on refining small, specific movements for every rep. “Jalen is going into year six now, so we’re looking for that 1 percent,” says Kelly. “He approaches every offseason the same, whether they won the Super Bowl or went out in the first round. There’s never a moment where he’s down or takes a rep off.”

Hurts describes his routine elegantly, as “saturating yourself in the details.” “Everything is found in the details,” he says. “Details and repetition. We’re all products of ingrained behavior—that’s through time on task, that’s repetition.” If he sounds like a coach, it’s intentional.

Joshua Kissi

Joshua Kissi

GET JALEN’S LOOK: Uniqlo shirt; ERL sweats; Jordan sneakers; Rolex watch; Hurts’s own jewelry.

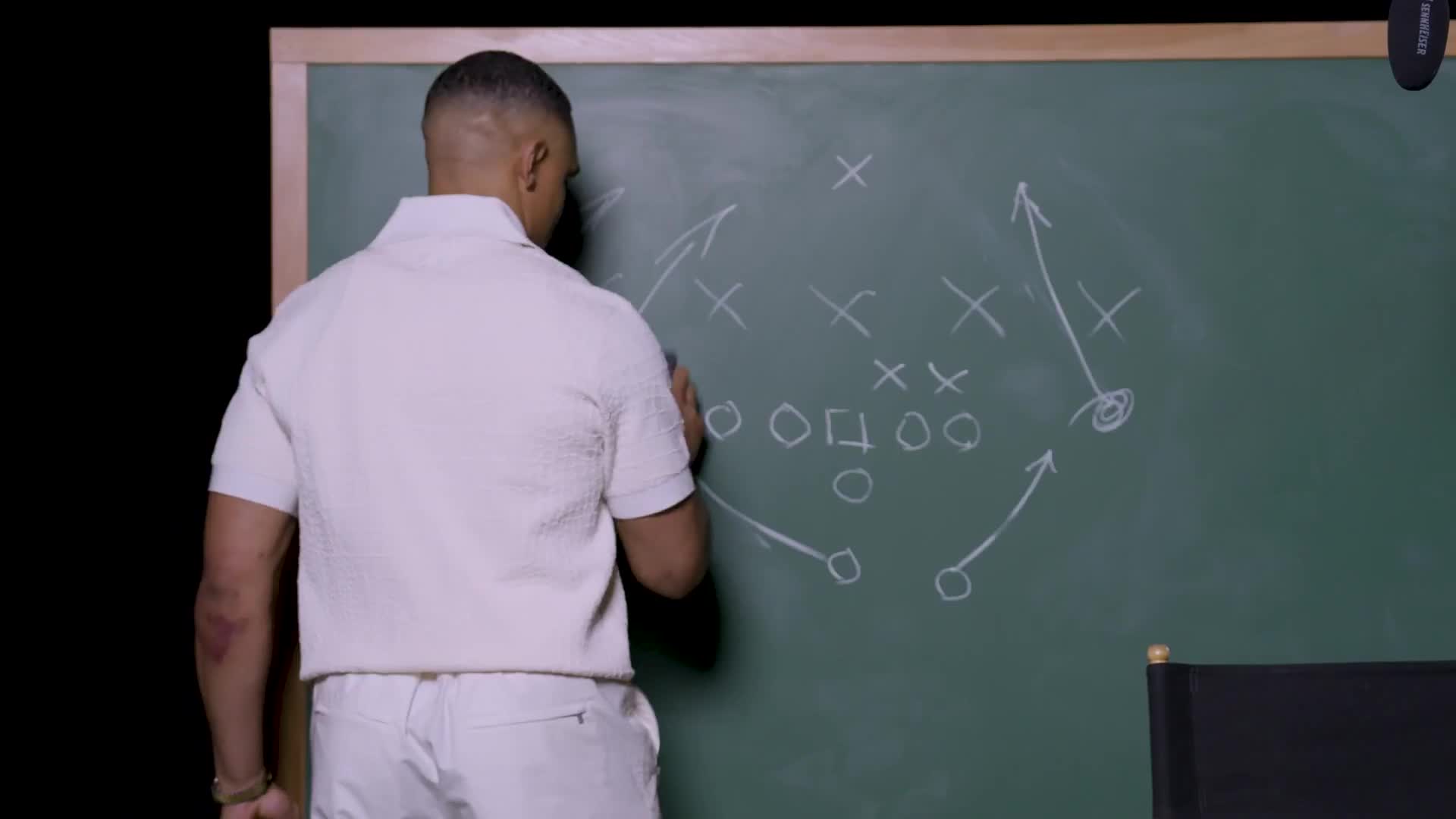

Mike Locksley, who worked with Hurts as Alabama’s offensive coordinator and still speaks with him regularly, says the biggest improvement he’s seen over the years is Hurts’s understanding of the game from a coach’s perspective. “We always talk about the mind of a coach, skill of a player. Everybody knows he can run, great arm talent. But the intermediate passing game, being able to throw the ball in tighter windows—those are functions of understanding what’s happening on the back end, the coverage,” says Locksley. “He’s putting together game plans in his mind before the season even starts: ‘These are the defensive structures that I faced a year ago. These are the blitzes that gave me issues. These are the throws I missed.’ ” Locksley has seen players commit to the technicalities, but not as meticulously as Hurts. “He’s approaching it as if every day somebody is trying to take his job,” he says. “He is a deep thinker, and he does not act emotionally. It’s his mental focus more than his mental toughness.”

Spend some time with Hurts and you quickly realize he’s a sound-bite specialist, but the public-facing part of his work seems to be tangential to him. As for what he represents as a player, he says, “It’s value and principle driven. It’s about what you perceive for yourself and the goals you set. None of those goals are influenced by what other people think. It’s about what I envision for myself. What I want to accomplish is just being the best version of myself. That’s literally it.” Half-smirk.

“Football is his priority,” says Joe D’Amelio, Klutch Sports Group’s SVP of football marketing, who brokered Hurts’s Jordan Brand, Beats, and Fanatics deals. “Jalen has always been super selective, strategic. He has positioned himself as being a face of the NFL in how he’s showed up, on and off the field,” citing Hurts’s ad promoting the 2028 L.A. Olympics as an example. His enigmatic Jalen sais quoi might be a plus. “Jalen’s 26, but you would think he’s 36,” says D’Amelio. “He hasn’t done too much, so people want to see him more.”

Hurts’s management team is, famously, made up almost entirely of women, led by his agent, Nicole Lynn, who negotiated his five-year, $255 million contract extension in 2023, which made him the highest-paid player in NFL history at the time. When the public lauded him for his contract, he tells me he didn’t quite know what to make of it. “Maybe I’m in my own little world—something that’s so normal to me ain’t that normal to everyone else.” He often feels like he’s playing a different game than everybody else. “That’s why I say everything is unprecedented. Un-ideal. Unordinary. Uncommon,” he says. “And defiant, in a sense. But that’s who I am.”

His meme-machine personality is resonating with football fans. Throw him a topic and he’ll have a line for it. Perfection? “It’s something you chase but never will conquer.” Success? “Every ounce of success is hidden in an abundance of work and effort.” Relationship tip? “Respect is earned, not given.” Knowing smile.

“UN-IDEAL. UNORDINARY. UNCOMMON. DEFIANT, in a sense. But that’s WHO I AM.”

He recycles his catchiest phrases in press conferences (see: “Let’s keep the main thing the main thing”), and he’s well aware that he tends to repeat himself. He sees it as a form of effective leadership: “It’s all in how you reach a person,” he reasons, adding, “Ten percent of life is what happens to you. Ninety percent is how you respond to it,” a quote from pastor and author Charles Swindoll. This style of speaking goes back to his father reiterating certain principles to him growing up: “Control what you can control.” The student has become the master, and he’s devising a lexicon of his own.

Unlike Patrick Mahomes—an Adidas guy and Swiftie by association—Hurts has aligned himself with Nike and Michael Jordan, the basketball icon with a Machiavellian game mentality. Hurts was zero years old when Jordan was leading the Bulls dynasty. Now, being a Jordan Brand athlete offers him proximity to the kind of greatness many young players would trade their single hoop earrings for. In early March, he and Jordan dined at a restaurant in Palm Beach, Florida—their first genuine one-on-one, says Hurts. He keeps the details of their sit-down private but says, generally, “I had moments where I was like, ‘Man, I didn’t know you thought about that that way.’ ”

So much of a quarterback’s career involves entanglements with fate. Hurts has figured out how to make game-changing plays. He’s said it for years—stats are subjective. “Football is like art,” he tells me. “Something subjective can be denied. But one thing that can’t be denied is winning.” He also finds ways to inspire teammates with his Jalenisms and what I see as a high emotional IQ. Earlier this year, a hot mic at Super Bowl LIX captured Hurts telling running back Saquon Barkley, the Eagles’ clutch 2024 addition, “You don’t understand the difference you made.” As a leader, Hurts says, “I’ve always believed you have to have your moments of sternness and your moments of accountability.” Then he channels his inner MJ and says, “I’m not gonna ask someone to do something I’m not willing to do. So we can talk about it within our roles. We can have a conversation. Because at the end of the day, I’m never gonna have a problem with someone who wants to win.”

By the end of our three hours, I can tell he’s not about to pass up an opportunity for an analogy that perfectly sums up his approach. I ask how he distracts himself from football during the offseason, if at all. He can’t risk injuring his back playing golf, so he’s taken up another strategy game: pool. He likes it because “you’re the ultimate puzzle solver,” he says. “There’s always a shot on the table. You gotta find it.” He continues: “I could bank it like this. I could hit it on the left side and put some English on the ball. There’s always an opportunity. Sometimes you gotta see it when it’s not even there.”

Joshua Kissi

Joshua Kissi

GET JALEN’S LOOK: Rick Owens shirt; Wales Bonner pants; Rolex watch; Hurts’s own jewelry.

Stylist: DexRob.Assistant Stylists: Kerrick Simmons And Rodney Williams.Barber: Berto Martin.Set Design: Andrea Huelse/Art Department.Production Assistant: Jess Beaudry/Kara Glynn Productions.Director: Dorenna NewtonDP: Elyssa AquinoEditor: Kyle OrozovichCamera: Derrick Saint Pierre

AP: Janie Booth

This story appears in the May-June 2025 issue of Men’s Health.

Clover Hope is a Brooklyn-based writer and the author of The Motherlode: 100+ Women Who Made Hip-Hop.