Limber up, dear reader: We’re going long on Boston Marathon trivia.

After 129 years of racing, the marathon has collected more than its share of factoids, lore and data points. Here are 26.2 facts about Boston’s most famous race.

Let’s get our blood pumping with a little non-Boston trivia. Why is this long race even called a marathon?

Because the Greeks won the battle of Marathon, beating a much larger Persian army.

According to the story from ancient Greek historian Herodotus, a soldier named Pheidippides ran the almost 25 miles back to Athens to deliver the good news before the city delved into chaos. He got there, cried out “Nike” (Greek for victory) and dropped dead.

Herodotus took a very Liberty Valance/”Print the legend” approach to history, so modern scholars aren’t sure the tale is true. But damn if that’s not a good story.

Now, I know what you’re probably thinking. “Just 25 miles? Then why are modern marathons 26.2 miles?” You’ll have to wait for the answer; this isn’t a trivia sprint.

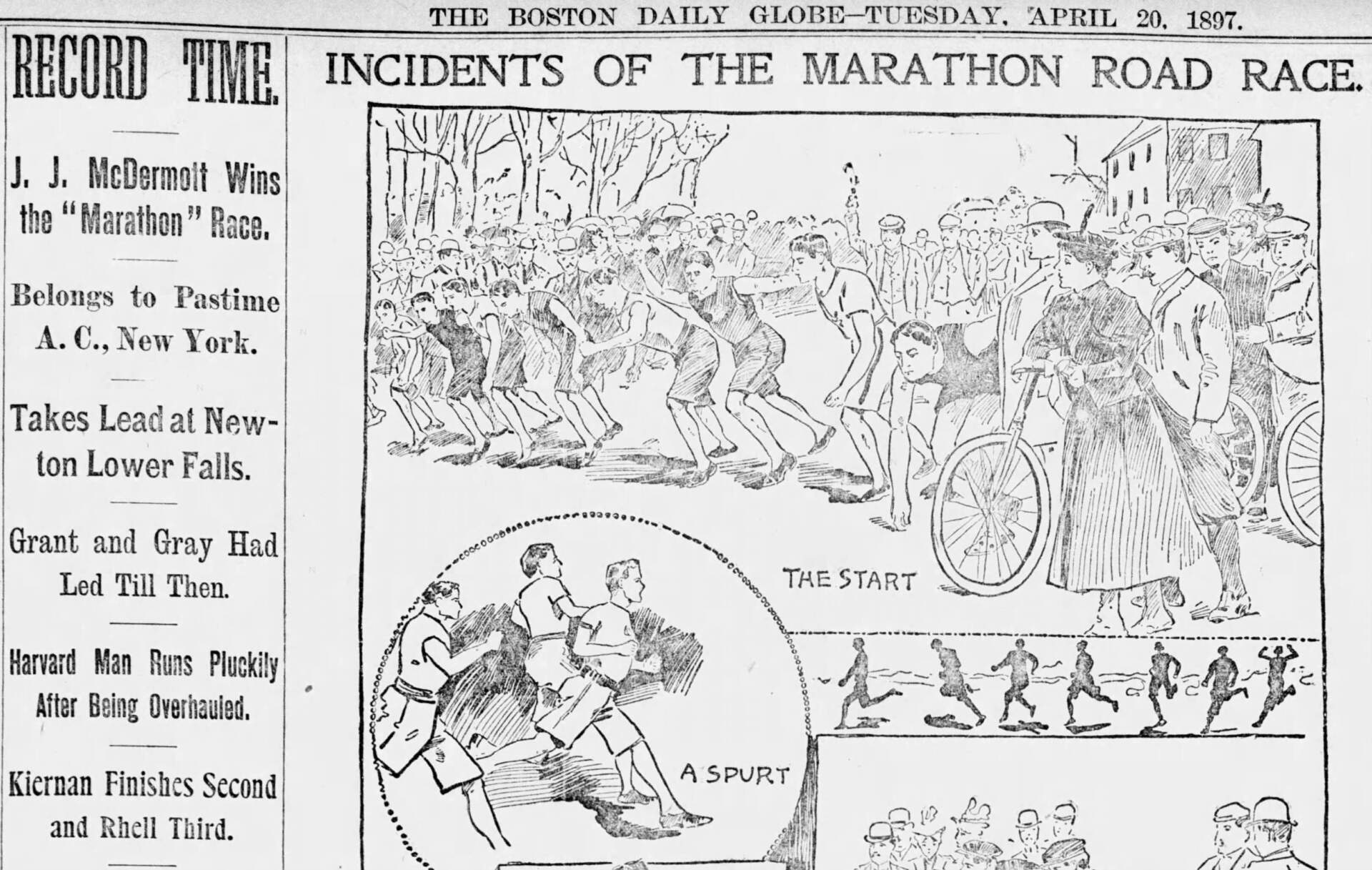

The modern marathon was born at the 1896 Olympics in Athens. Almost immediately, plans were hatched for a similar distance run in Boston. Eighteen men lined up in Ashland on April 19, 1897 to run the inaugural “American Marathon,” which ended somewhere around Boston’s Copley Square.

A page from the Boston Daily Globe’s coverage of the first Boston Marathon in 1897.

Maybe it’s because it was first, maybe it’s because it’s so hard, maybe it’s because of the crowds. But Boston is one of the major races in marathon running. For years, Abbot World Marathon Majors‘ “big six” included Boston, Berlin, Chicago, London, New York and Tokyo as the sort of grand-slam-plus of the sport. People who run all six can earn the six star medal. But there’s now a seventh big race on the scene: Sydney was added as a world major in 2025. Abbot is also evaluating proposals to add Cape Town and Shangai’s races to the club.

With more than 30,000 runners each year, the competition to qualify for the Boston Marathon is intense. If you want to qualify for the 2026 race, a man aged 18-34 must run a marathon of 2 hours, 55 minutes or faster in the qualifying window — a massive accomplishment for most amateurs. You can see the Boston Athletic Association’s official chart for qualifying times here.

What to do if you aren’t able to qualify? You can try and raise some significant cash for one of the Boston Marathon’s official charity partners. Each charity has its own minimum fundraising request, with some asking runners to scrounge up more than $10,000 for one of their coveted bibs. In 2025, there are 176 participating nonprofits.

OK, you can’t run a sub-three-hour marathon and you didn’t raise enough dough for an official charity. What to do? Some will forego the official race bib and run as a an unsanctioned runner on the course — a bandit, if you will. As Boston.com explained in 2020, bandits are not exactly welcome and highly frowned upon on the course. Still, many do raise money for charity and others are in it for the fun.

The marathon route may feel like it’s chiseled in stone, but it’s changed a lot over the years. The first Boston Marathon started in Ashland — one town east of its now-famous starting line in Hopkinton — for the race’s first 26 years. It also ended in a different place, but we’ll get to that later.

A sign on the Hopkinton Common marks the town as the Boston Marathon’s official starting point. (Suzanne Kreiter/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

For a race filled with history, the Boston Marathon still finds ways to add to its lore. A more recent entry is Spencer, the golden retriever and goodest of boys that would stand roadside in Ashland and cheer on runners, “Boston Strong” flags in maw. He passed away in 2023, but a statue of his friendly gaze watches over the racecourse today.

He’s also inspired a gathering of goldens on Boston Common, the photos of which will melt the coldest of hearts. Alas, the gathering was canceled for 2025, but organizers hope to return the pups to America’s oldest public park in the future.

Spencer, a therapy dog from Holliston, was named the Official Dog of the 126th Boston Marathon in 2022. His statue faces marathon runners as they enter Ashland along Route 135. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

For decades, the Boston Marathon was an all-male affair. Bobbi Gibb changed that in 1966. As the BAA tells it, Gibb hid in some bushes near the starting line and jumped into the race after the gun fired. She’s the first known woman to run and finish the race.

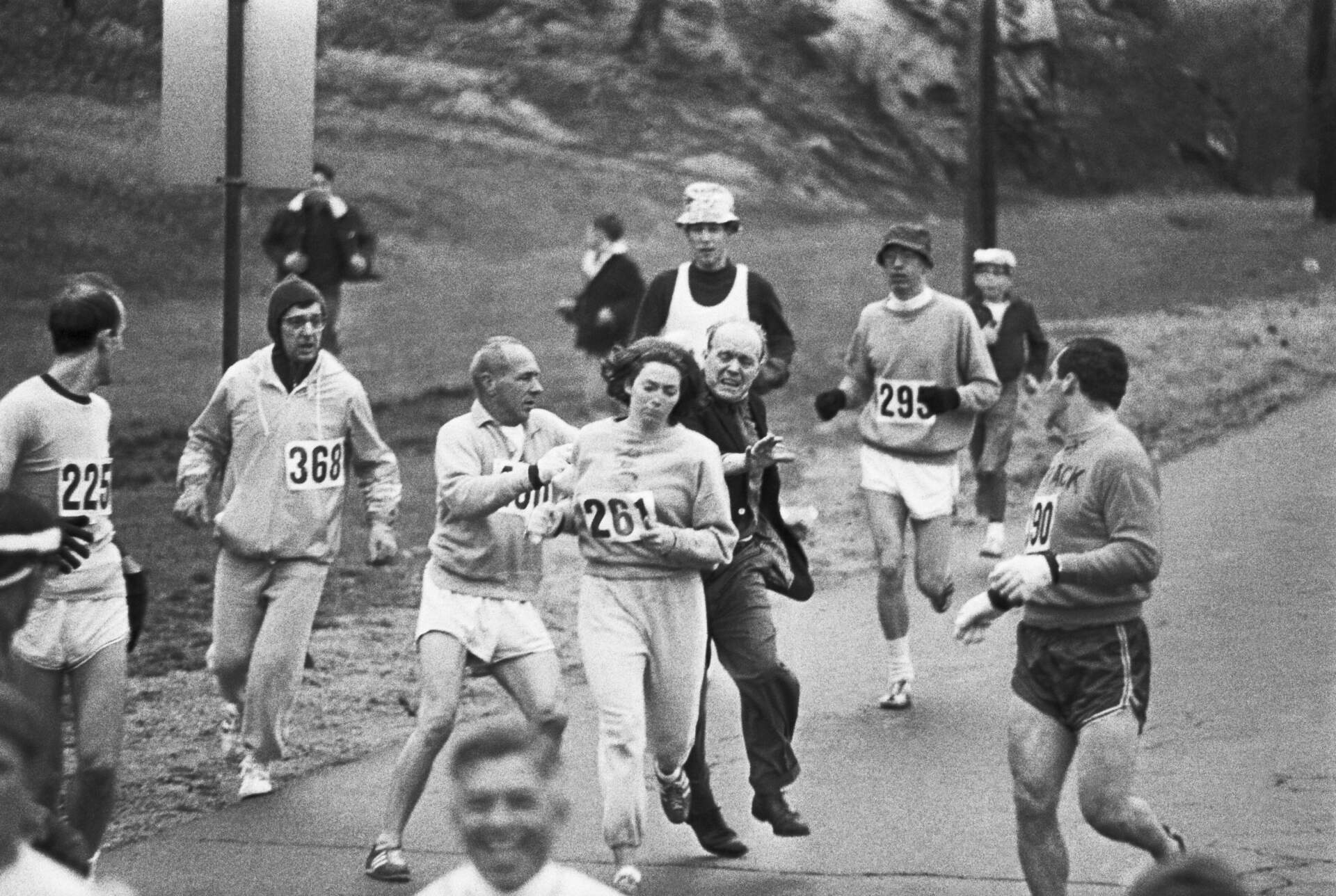

In 1967, Kathrine Switzer took things a step further, and registered to run as “K. W. Switzer.” She secured her bib and started the race, but when officials realized she was a woman, they chased her on the course and tried to physically remove her. She was undeterred, and fellow runners came to her aid, leading to some of the most dramatic photos in race history.

Trainer Jock Semple tries pull Kathrine Switzer out of the 1967 Boston Marathon as fellow runners move in to form a protective curtain around her. (Getty images)

Runners block trainer Jock Semple as he tried to pull Kathrine Switzer out of the 1967 Boston Marathon. (Getty Images)

Kathrine Switzer continues to run the 1967 Boston Marathon after trainer Jock Semple tried to pull her off the course. (Getty Images

After the BAA relented and created a women’s division in 1972, they would refer to those early times as the “unofficial era.” But as the years went on and race officials embraced the contributions of Gibb, Switzer and other early female runners to the sport, they renamed the period the “pioneer era.”

Switzer told Boston.com that she and the man in the photos, Jock Semple, would later reconcile, and that he became a supporter of women marathoners.

In 1975, Boston was the first major marathon to create a wheelchair division. According to the BAA, racer Bob Hall made a bet with then-race director Will Cloney: If he could finish the course in less than three hours, his race would be certified. Hall crossed the finish line with two minutes to spare.

Bob Hall shakes hands with Ernst Van Dyk after he won the men’s wheelchair division of the 110th Boston Marathon. (Matt Stone/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald via Getty Images)

There’s prize money for the winners and some top finishers at the Boston Marathon, thought it’s not the same for every division. In the open divisions, the men and women’s winners each get $150,000, with lower prize purses for other finishers. In the wheelchair division, it’s $50,000 for first place. Masters (runners over 40) get $5,000. And winners in the different para divisions get $3,000 each.

That’s a lot to remember, so here’s the BAA’s official prize money chart.

But wait, there’s more: You can earn a big bonus if you set a course record in the open or wheelchair divisions.

There’s no shortcut in a marathon. But at least one Boston Marathon runner dared to ask: What if there is?

So goes the tale of Rosie Ruiz, a novice runner who was the first women to cross the finish line in 1980, shattering her own best time set months earlier in New York.

Almost immediately, people started asking questions. Ruiz was a complete unknown to the then-small distance-running community, which is no great sin but made her winning an elite race … unlikely. She was dressed in a heavy shirt that had some sweat on it, but not the drenching you’d expect after two-and-a-half hours of running. And when racing legend Switzer asked her some basic-for-runners questions about interval training, Ruiz had no answers.

Soon, it was alleged that Ruiz found a shortcut, leaving the course; witnesses claimed they saw her hop back into the race somewhere near Kenmore Square. The runner denied it. After an investigation, Ruiz was disqualified and became synonymous with cheating.

[Looking for your own shortcut? Click here to take the Green Line to the Kenmore Square section of this list.]

Eight, in fact. Hopkinton, Ashland, Framingham, Natick, Wellesley, Newton, Brookline and Boston. Here’s a map:

It’s no small inconvenience to close 26-plus miles of road in Massachusetts. But lest you think your time in the resulting traffic is worthless, remember that the marathon brings bucks to the commonwealth.

Like, big bucks.

The state brought in about $500 million in increased business around the marathon in 2024, according to an analysis by the University of Massachusetts Donahue Institute. Most of the runners and more than half of the spectators at the 2024 race came from outside of Massachusetts. And the race and race-related events required around 2,900 jobs.

For most long-time marathon watchers, two of the most familiar faces in the race belonged to the late Rick and Dick Hoyt, the father-son duo who inspired racers and viewers alike for 32 years. Dick would run the entire marathon pushing his son, Rick, who had cerebral palsy, in his special racing chair.

Rick and Dick Hoyt, Boston Marathon stalwarts, by the Hamilton Reservoir behind their home in Holland, Mass. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Here’s another recent tradition: Each year, volunteers plant thousands of daffodils along the marathon route. The flowers are a reminder of the lives lost and changed following the 2013 bombings near the marathon finish line.

Runners pass blooming daffodils in Boston as they head toward buses that will transport them to the starting line in Hopkinton, Mass., for Boston Marathon in 2017. (Charles Krupa/AP)

Ask most people, and they’ll tell you Heartbreak Hill got its name from all the runners who abandon their race when encountering this mile-20 behemoth. That’s a perfectly reasonable thing to believe, but it’s not true.

The hill earned its moniker thanks to a classic battle between two of the race’s greats. Indigenous runner Ellison “Tarzan” Brown, of the Narragansett tribe, had led much of the 1936 race, but was caught on the last and steepest of the Newton Hills by two-time race winner Johnny Kelley. As he passed, Kelley gave Brown a pat on the back.

We’ll never know whether Kelley meant that as a friendly or condescending gesture. But we do know what happened next.

Brown “ran like a bat out of hell” and surpassed Kelley to win the race. The loss, it’s said, broke Kelley’s heart and gave the hill its name. It also landed Kelley a statue at the base of “Heartbreak Hill,” memorializing his running career.

Ellison M. “Tarzan” Brown, a 22-year-old a member of Rhode Island’s Narragansett tribe, breaks the tape to win the 1936 Boston Marathon. (File photo/AP)

Runners pass the 25-mile mark as they enter Kenmore Square, a sure sign the end of the race is at hand. A block away, the Red Sox always play a late-morning game at Fenway Park at the same time. The team will cut to a live shot of the race on one of the stadium’s video boards, and passing runners have said they can hear the 30-odd thousand fans roar in support. Since 2021, the players wear yellow and blue uniforms to match the marathon’s official colors.

The elite runners are long-gone by the time the game ends, but amateurs are often greeted by thousands of cheering baseball fans who flood into the square. Speaking of Fenway …

Is this strictly a marathon fact? No. Did it happen on Patriots’ Day, AKA Marathon Monday? Yup. That’s good enough reason to share Don Orsillo and Jerry Remy’s 2007 “Here comes the pizza” gigglefest:

These are the last two turns on the current Boston Marathon route, and the expression has taken on a meaning of expectation and achievement. It’s also a place where beleaguered racers can sometimes make a costly mistake, following service vehicles down Commonwealth Avenue and missing that first crucial turn. That happened to seven-time marathon winner Marcel Hug in 2021. Thankfully, he was able to double back and win the race, but missed a chance to set a new course record and earn a $50,000 bonus.

It’s one of those bits of pop wisdom that turns out to be true: Loading up on carbohydrates really does help runners, according to food scientists. Lots of marathoners have their own preferred ways to fuel up before a race. And Boston steps up to get runners the starches they need, with several restaurants offering pasta deals. Even City Hall got into the tradition in years past, offering pasta dinners the night before the race.

Boston Mayor Tom Menino serves pasta to a runner during City Hall’s pre-race dinner in 2004. (Justine Hunt/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

With its mid-spring scheduling and geographic latitude, the Boston Marathon should fall into that sweet spot of not too hot, not too cold.

That’s the theory, anyway. But in practice? Spring in Boston is a total Jekyll and Hyde experience.

On the one end, it can get downright frigid, like in 1926, when the high temperature was 28 degrees, according to meteorologist Danielle Noyes. Or it can go the other way, like in 1905, when the temperature topped 100 degrees.

We haven’t even gotten to precipitation. In 2018, some runners developed hypothermia as they slogged through frigid rain and temperatures in the 30s.

As always for a Massachusetts April, wear layers and adjust accordingly.

(Danielle Noyes/1°Outside)

There have been plenty of thrilling sprint finishes in Boston Marathon history, but perhaps the most famous is 1982’s “Duel in the Sun,” where American runners Alberto Salazar and Dick Beardsley spent close to half the race just feet apart, far ahead of the field. By the time the pair made it to Hereford Street, they were sprinting and broadcasters Bob Lobel, Switzer and Jack Williams could not contain their excitement.

Yeah, that famous sprint finish ended on Ring Road, not Boylston Street. And Ring Road wasn’t the first finish line either. That was located … somewhere … in Copley Square. Runners in 1897 ran a lap around Irvington Oval in Boston, but the exact location was never recorded and remains a mystery, according to Runner’s World magazine.

A couple of years later, the line was moved to the front of the BAA’s new headquarters at Boylston and Exeter streets, where it remained until 1964. That’s when things got shifted to Ring Road — cue the duel — until 1985, when the finish line settled in front of Boston Public Library on Boylston Street.

Ernst Van Dyk is the unquestioned king of the Boston Marathon. He’s won a whopping 10 Bostons in the men’s wheelchair division.

Jean Driscoll has nabbed eight Boston victories in the women’s wheelchair division.

American Clarence DeMar dominated the men’s open race, winning seven times between 1911 and 1930. Then, there are a slew of four-time men’s winners in more recent, competitive times, including Robert Kipkoech Cheruiyot and Bill Rodgers.

In the women’s open race, Catherine Ndereba has won four times. Some marathon giants, including Gibb, Sara Mae Berman, Utta Pippig and Fatuma Roba, have won three times.

The handcycle division is fairly new, having started in 2017. In that time, Tom Davis and Alicia Dana have each won the race three times.

After decades of being an American affair, the Boston Marathon has become an international event, with winners from around the world. But if you’re a homer, you’ve had some relatively recent successes. Meb Keflezighi won the men’s open race in 2014, and Des Linden won the women’s open race in 2018. Daniel Romanchuk won the mens wheelchair division in 2022 and Susannah Scaroni won the women’s division in 2023. Every handcyclist winner has been American.

Meb Keflezighi celebrates his victory with an American flag after the 118th Boston Marathon April 21, 2014 in Boston. (Charles Krupa/AP)

Desiree Linden crosses the finish line to win the women’s division of the 122nd Boston Marathon on April 16, 2018, in Boston. (Elise Amendola/AP)

The Boston marathon, with its killer hills, is unlikely to ever see a modern world record set. For men and women in the open division, the current world records were set at the far flatter Chicago Marathon, where Kelvin Kiptum ran an eye-popping 02:00:35 in 2023, and Ruth Chepng’etich ran 02:09:34 in 2024.

So, who’s run Boston faster than anyone else? Here are the records by division:

- Men’s open: Geoffrey Mutai (2:03:02 in 2011)

- Women’s open: Buzunesh Deba (2:19:59 in 2014)

- Men’s wheelchair: Hug (1:15:35 in 2024)

- Women’s wheelchair: Manuela Schär (1:28:17 in 2017)

- Men’s handcycle: Davis (0:58:36 in 2017)

- Women’s handcycle: Dana (1:15:20 in 2024)

Congratulations, you just ran your Boston trivia marathon. We’ll give you one more non-Boston fact as you wrap yourself in a mylar blanket and chug some Gatorade.

Why is there that extra point-two miles in a marathon?

Because it’s good to be the king.

The 26.2 mile distance was cemented at the 1908 Olympics in London. As the BBC tells it, the royal family requested the race start at Windsor Castle and end in front of the royal box at White Stadium, so, you know, the fancy folks could get the best view of things.

Boston didn’t adopt the 26.2 mile distance until 1924.